Blueprint for an Options Machine

Exiting the Income Class: Part Two

Why am I obsessed with building wealth systems?

Raised in a Navy family in Newport, Rhode Island, I grew up surrounded by people living a very different life. A much wealthier one.

Not the other folk on the military base.. I’m talking about the ones who owned the sailboats and the summer homes on the hills around the base. The people living around me had resources, and I could recognize the difference between selling your time for money, and selling access to your assets for money.

I wanted to be in the Capital Class, not the Income Class.

So I started my career on Wall Street in investment banking. It was a grind. It was a baptism by fire. But it taught me the language of money.

From there I co-founded a hedge fund called Throne Capital. We didn’t just read financial statements. We built machines to read them for us. We scraped data. We automated analysis. We looked for the signal in the noise.

I learned that a business is just a system. It is a collection of inputs and outputs. If you engineer the system correctly you get efficiency. You get reliability. You get revenue. You need to build systems to enter the Capital Class and bypass the linear time-for-money world of the Income Class.

Some people instinctively know this, and they focus their efforts accordingly.

If you don’t get the divide between the Income Class and the Capital class, start here:

My current focus is building an amazing company with a small group of talented people, and my family office, the “Holding Company” for my wealth system. I am a first-generation wealth builder. I view my capital allocation through the lens of a systems architect. I use intensity, consistency and resilience to incrementally build leverage across multiple dimensions.

A significant portion of my portfolio is allocated to venture capital. I love the asymmetry of venture. I love building things. But venture capital has a massive flaw.

It has negative liquidity.

I write checks to startups. Then I work with them to upgrade their revenue engine, their GTM strategy, their technology strategy, and all related areas. I write follow-on checks. I provide more advice and wait some more. It can take seven to ten years to see a return. The fastest I’ve ever gotten money back was two years. Meanwhile, my operating expenses continue. Life continues. Bills pile up.

I needed to engineer a solution to ensure my family office had positive cashflow to offset the capital intensiveness of angel investing.

I needed a wealth engine with positive liquidity. I needed a system that generated cash flow today to offset the capital calls of tomorrow.

I did not want to day trade. I did not want to stare at charts. I wanted to build a machine.

That machine is selling options.

The Philosophy of the House

Most people treat the stock market like a casino. They walk in and put their money on red. They buy a stock hoping it goes up. They buy a call option hoping for a moonshot.

They are the gamblers.

Gamblers occasionally win big. Usually they bleed out slowly.

I am not a gambler. I am the House.

When you build an options machine you stop trying to predict the future. You start selling insurance on it.

Think about how an insurance company works. GEICO does not know if you specifically will crash your car this year. They do not care. They know that statistically, across a pool of one million drivers, a certain number will crash. They price the premiums to cover those crashes and leave a healthy profit margin.

They sell time. They sell peace of mind. They sell risk transfer.

That is exactly what we do when we sell options. We become the insurance company.

We sell time. We sell the willingness to take on risk at a specific price.

The buyer of an option is paying for the privilege of transferring risk to you. They are paying a premium for it. That premium is our cash flow.

This shift in mindset is the most important step. You are no longer betting on stock direction. You are harvesting the difference between implied volatility and realized volatility.

You are getting paid to wait.

The System Requirements

Before you turn the machine on you need to understand the constraints.

To run this machine effectively you need three things.

1. Capital This strategy requires money to make money. It is capital intensive. You need enough capital to secure the puts you write and hold the shares you get assigned. If you are trying to turn $5,000 into $100,000 in a month this is not for you. This is for wealth preservation and steady compounding.

2. The Underlying Assets You cannot run this machine on garbage. You cannot sell insurance on a burning building. You must only interact with high-quality, liquid assets. These are companies or ETFs you would be happy to own for the next ten years. If you wouldn’t hold the stock you have no business writing options on it.

3. Emotional Discipline The market is manic-depressive. The machine must be cold and rational. You will see red days. You will see positions go against you. The system only works if you stick to the rules when it feels uncomfortable.

Most people have a weakness: themselves.

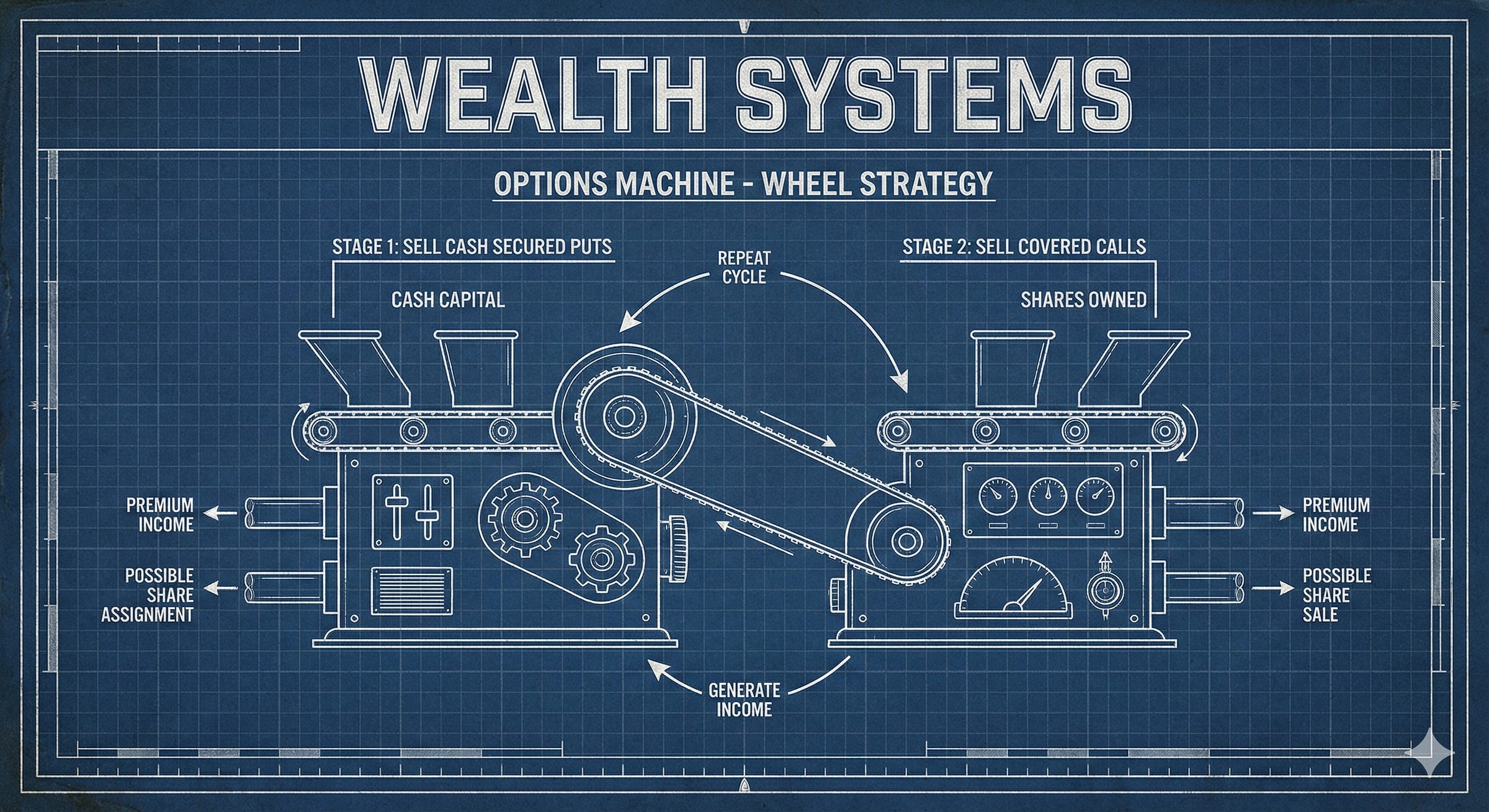

The Wheel Strategy

There are many ways to trade options. But for a family office looking for consistent cash flow, “The Wheel” is the gold standard.

It is a cyclical system. It loops. It feeds itself.

The Wheel consists of two primary mechanisms working in tandem. The first is the Cash-Secured Put. The second is the Covered Call.

Let’s break down the blueprint.

Phase 1: The Acquisition Layer

Most investors buy stocks at the current market price.

If Apple is trading at $175 they pay $175.

That is inefficient and NOT at all how the professionals do it.

I rarely buy a stock at market price. Instead I write a Cash-Secured Put.

When I write a put option I am entering a contract. I agree to buy the stock at a specific price (the strike price) by a specific date. In exchange for this promise the buyer pays me cash immediately.

This is the premium.

Let’s look at the mechanics.

Suppose I want to buy Stock X. It is currently trading at $100. I am happy to own it at $100 but I would prefer to own it at $95.

I write a put option with a strike price of $95 that expires in 30 days.

The market pays me $2.00 per share for this contract. Since one contract covers 100 shares I collect $200 instantly.

Two things can happen.

Scenario A: The stock stays above $95. At expiration the stock is trading at $98. The option expires worthless. I keep the $200 premium. I do not own the stock. My cash is freed up. I simply reload the machine and write another put. I have generated a return on my cash without ever owning the asset.

Scenario B: The stock falls below $95. At expiration the stock is trading at $92. I am obligated to buy the stock at $95.

Most people view this as a loss. I view this as a successful acquisition.

Remember the math. I agreed to buy at $95. But I was paid $2.00 upfront. My effective cost basis is not $95. It is $93.

I acquired a high-quality asset at a discount to the price I was originally willing to pay. Plus I got paid to wait for it.

This is the “Acquisition Layer” of the machine. We are getting paid to set limit orders. Not bad.

But it gets better!

Phase 2: The Monetization Layer

Once I am assigned the stock the machine shifts gears. I now own 100 shares of Stock X with a cost basis of $93.

I do not just let the stock sit there. I put it to work. I rent it out.

I write a Covered Call option against my shares.

This is the inverse of the put. I am now agreeing to sell my stock at a specific price by a specific date. In exchange I collect another premium.

Let’s continue the example. Stock X is at $92. My basis is $93.

I write a call option with a strike price of $95 expiring in 30 days. The market pays me $1.50 for this contract.

I pocket the $150.

Again two things can happen.

Scenario A: The stock stays below $95. The option expires worthless. I keep the $150 premium. I still own the stock. I lower my cost basis further.

Originally my basis was $93. I just collected $1.50. My new adjusted cost basis is $91.50.

I repeat this process every month. I keep collecting rent. I keep lowering my basis.

Scenario B: The stock rises above $95. The stock rallies to $100. My shares are called away. I am obligated to sell them at $95.

Let’s look at the P&L of the full cycle.

I received $2.00 for the put.

I bought the stock at $95.

I received $1.50 for the call.

I sold the stock at $95.

Capital Gain on stock: $0 (Bought at $95, Sold at $95). Premium Income: $3.50. Total Profit: $350 per contract.

Now the cycle is complete. I have cash again. I go back to Phase 1. I find a new target or the same target and start writing puts again.

This is the Wheel. It turns capital into cash flow. It turns patience into profit.

Engineering the Machine

A machine is only as good as its calibration. You cannot just pick random strike prices and expiration dates. You need data.

As a systems guy I look at the “Greeks.” These are the variables that determine the price of an option.

The two most critical variables for this machine are Delta and Theta.

Delta: The Probability Gauge

Delta tells you how much an option’s price moves relative to the stock price. But it serves a more useful function for us. It is a proxy for probability.

A Delta of 0.30 roughly translates to a 30% chance that the option will expire “in the money.”

When I write puts I usually target a Delta between 0.20 and 0.30.

This means I am choosing a strike price that has roughly a 70% to 80% chance of expiring worthless.

I want to win the majority of my trades. I want the premium. I only want to take ownership of the stock if there is a significant correction.

If you get greedy and sell high Delta puts (closer to the current price) you collect more premium. But you will get assigned stock constantly. You will be catching falling knives. Be sure to wear gloves.

Stick to the 0.20 to 0.30 Delta range. It is the sweet spot of risk and reward.

Much less pointy.

Theta: The Time Decay

Theta measures how much value an option loses every day as it approaches expiration.

This is our product. We are selling Theta.

Time decay is not linear. It accelerates. An option loses value much faster in the last 30 days of its life than it does in the first 30 days.

This is why I typically write options with 30 to 45 days until expiration.

This timeframe places us on the steepest part of the decay curve. The value of the contract melts away rapidly. That is good for us as sellers. We want the value to go to zero.

If you sell weekly options you are collecting pennies and taking on too much “gamma” risk (rapid price swings). If you sell yearly options the time decay is too slow.

30 to 45 days is the best risk/reward point, the optimal frontier.

But is The Wheel the optimal strategy if return on equity is your goal?

The Wheel is capital intensive. Nothing is perfect.

To write a put on a $200 stock you need $20,000 in cash collateral.

Sometimes we want to optimize for capital efficiency. We want higher returns on equity.

No, for that, you will need another tool…