The Unstoppable Money Printer Meets Absolute Scarcity

The first thing you have to understand is that the number doesn’t make sense. The number is one quadrillion dollars. $1,000,000,000,000,000.

That’s a one with fifteen zeros after it.

It’s the sort of number that astronomers use to measure the void, not a number you’re meant to find down here on Earth. It’s the estimated value of the global asset market, all the stocks, all the bonds, all the real estate, all the slivers of ownership in every conceivable enterprise, all tallied up.

And it’s a lie.

Not a deliberate, mustache-twirling lie, but the kind of lie that evolves organically, out of a series of perfectly reasonable decisions made by very serious people in very nice suits. It’s the kind of lie you tell yourself when the alternative is too terrifying to contemplate. The lie is that the quadrillion dollars represents a quadrillion dollars’ worth of stuff. Of productive capacity, the current value of future earnings, of shelter, of utility. The truth is that a huge, unquantifiable chunk of that number is something else entirely.

It’s a ghost in the economic machine. It’s the stored energy of excessive central bank money printing. It is the global monetary premium, and it’s the single most important, and least understood, force in the world.

To find the modern ghost’s origin story, you have to go back to the fall of 2008. To get at heart of the fiat matter you need to go further back than that…. but let’s take it easy for this one and begin our analysis in 2008.

The global financial system had, to use the technical term, gone completely haywire. The machine that was supposed to allocate capital and price risk had turned into a doomsday device, and its primary output was fear. In the face of Armageddon, the world’s markets ablaze, the central bankers did the only thing they could think of to do: they turned on a firehose.

They called it Quantitative Easing, or QE, a name so bland and technical it felt designed to put you to sleep. But what it meant was anything but boring. It meant they were creating money (trillions of dollars of it) out of thin air and pumping it into the financial system to keep it from seizing up.

The first rule of finance, and of life, is that when you have a problem, you throw money at it.

The central banks, led by the U.S. Federal Reserve, were now running the biggest experiment of this kind in human history. The plan wasn’t really a plan; it was an act of desperation. It was financial CPR.

But here’s the funny thing about turning on a firehose in a sealed room: the water has to go somewhere. The money wasn’t just vanishing. It was sloshing through the plumbing of the global economy, seeking a container.

You couldn’t just leave it in a checking account; the whole point of the exercise was that the value of cash was being deliberately, systematically eroded. The interest rates were nailed to the floor. Leaving your money in cash was like storing ice cubes in the sun. You were guaranteed to have less tomorrow than you had today, in terms of purchasing power.

So, where did it go?

It went everywhere. It flooded into the stock market, pushing the S&P 500 to new, dizzying, logic-defying heights. It drenched the bond market, creating the strange situation where investors would pay governments for the privilege of lending them money. It poured into real estate, transforming quiet residential neighborhoods in Austin and Boise into speculative battlegrounds. It found its way into fine art, classic cars, luxury watches, and rare bottles of wine. Any object that was even remotely scarce became a vessel for this ocean of new money.

The price of everything that could go up, did go up.

And so the great quadrillion-dollar lie was born. A house in Vancouver wasn't suddenly worth $2 million because it provided ten times more shelter than it did a generation ago. An S&P 500 index fund wasn't worth four times its 2009 value because American corporate genius had quadrupled in a decade. These assets were repriced upwards because they were acting as sponges. They were soaking up all that excess liquidity. They had acquired a monetary premium. Their price was no longer just a reflection of their utility; it was a reflection of their ability to serve as a life raft in a sea of managed inflation.

They became, in effect, money. Bad money, but the only money people could find.

It was a strange sort of magic. And like all magic tricks, it relied on the audience not looking too closely at the man behind the curtain, who in this case happened to be the chairman of the Federal Reserve. The system worked, for a time. It staved off collapse. But it created a new, quieter problem. The entire global financial system was now balanced precariously on this assumption: that you could continuously inflate the supply of money without ever facing a reckoning.

That you could forever store this monetary energy in assets that were never designed to hold it. Everyone’s retirement, their property values, their entire net worth, was predicated on the idea that these leaky, imperfect sponges would never become saturated.

And here is where our story truly begins. Because at the very same moment the old system was being bailed out, at the height of the panic, in the dark winter of early 2009… a new idea was quietly born.

On January 3rd, 2009, a person or group of people known only by the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto launched a peculiar piece of software. It was a peer-to-peer electronic cash system.

He, she, or they called it Bitcoin.

It came with no marketing budget, no corporate headquarters, no celebrity endorsements. It was announced on an obscure mailing list for cryptographers. It was, to almost everyone on the planet, a complete non-event. But baked into the very first block of transactions, the "Genesis Block" was a small, hidden piece of text. It was a headline from that day's edition of The Times of London: "Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks."

It wasn't a coincidence.

It was a mission statement.

It was a digital fossil, a timestamp that forever linked Bitcoin’s creation to the precise failure of the traditional financial system. It was a quiet, elegant, and devastatingly profound act of protest. Satoshi had a viewpoint, not just an engineering & game theoretic mega mind.

The problem with the old system, as Satoshi saw it, wasn't just its corruption or its recklessness. The problem was structural. It was the firehose itself. The fact that a small group of people, accountable to no one, could decide to turn it on whenever they felt it necessary was not a feature, but a bug.

The value of everyone's money rested on the whims and political pressures acting on a handful of central bankers.

Satoshi’s creation was a direct answer to this problem. It was an attempt to build a form of money that was immune to them.

To do this, Satoshi invented something new. Something that had never before existed in the history of the world: absolute scarcity.

Humans have always valued scarce things. Gold is scarce. Naturally occurring flawless diamonds are scarce. A beachfront property in Malibu is scarce. But this scarcity is always relative. If the price of gold triples, mining companies will pour billions of dollars into finding more of it. They will reopen old mines, sift through tailings, and invent new technologies to extract it from the earth. The supply of gold, while difficult to increase, is not fixed. It responds to human effort. It is elastic. It stretches when forces pull it.

Bitcoin is different.

Satoshi designed Bitcoin’s supply to be completely, totally, and algorithmically insensitive to demand. The rules were set in stone from the first line of code. There would only ever be 21 million Bitcoin. Not 21 million and one. Not a few more if the price got really high. Not a few less if it crashed. Twenty-one million. Period. The number was arbitrary, but its finality was everything.

The schedule of its creation was also fixed.

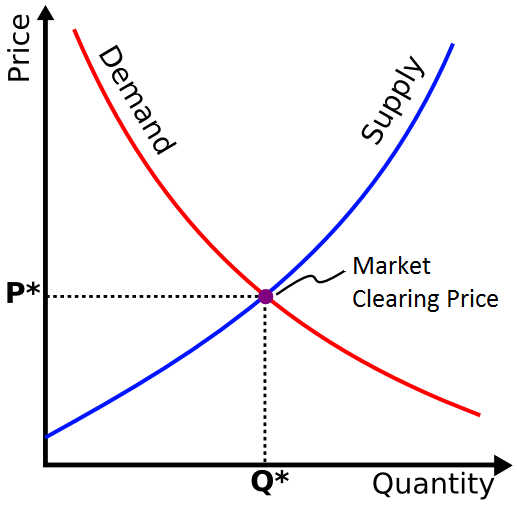

A certain number of new coins are "mined" roughly every ten minutes, and that number is cut in half approximately every four years in an event known as "the halving”. This process will continue until the last fraction of a coin is mined sometime around the year 2140. After that, the supply becomes perfectly inelastic. The supply curve is a vertical line. It means the supply doesn't give a damn what you want. No amount of money, no amount of computing power, no amount of human ingenuity can create new Bitcoin any faster than the protocol allows. It’s as if, on the first day, a cosmic law was passed, and there is no appeals court.

This had never happened before.

Bitcoin is a form of money whose supply is governed by mathematics, not by men in suits. It is the polar opposite of the system of Quantitative Easing. The Fed could create a trillion dollars with a few keystrokes at a Tuesday meeting. The Bitcoin network would continue its slow, predictable, unchangeable march towards 21 million, indifferent to the chaos of human affairs. It was a rock thrown at the hornet’s nest of modern finance back in 2009 and the world is just starting to realize the implications.

For the first decade of its life, this was mostly a curiosity, a playground for geeks, libertarians, and a handful of speculative traders. It was interesting. It was weird. But it wasn't important. The numbers were too small to matter.

But the firehose was still on. Year after year, the water level of global liquidity kept rising. A $600T asset bubble swelled into a gargantuan quadrillion-dollar monetary premium mega bubble over just the last 10-years, alone. Tell me: do you feel your personal wealth doubled in the last decade? No, didn’t think so. The world’s “wealth” seemingly DID double. Strange, eh?

The sponges (remember: stocks, bonds, real estate, art, gold) were becoming saturated. They were struggling to hold all that value that never made its way to you. People began, slowly at first, and then with gathering urgency, to look for a better sponge. A perfect sponge. Something that didn't leak. Something that couldn't be diluted.

We have, on one side, the largest pool of desperate, searching capital in human history. A significant portion of that $1 quadrillion global asset market, all that monetary premium created by years of inflation, is fundamentally energy seeking a stable container. On the other side, we have an object of absolute, unyielding scarcity. A container with a fixed volume of 21 million units, whose walls are made of mathematics and cannot be stretched.

The question is not "Will the price of Bitcoin go up?"

That is a trivial question.

The real question is far more important: what are the economic, social, and political consequences when a virtually infinite force of demand, born from a failing monetary system, collides with an object of perfectly finite, inelastic supply? What happens when all that energy, all that monetary premium, tries to cram itself into this tiny, unyielding digital box? It is a scenario without precedent.

It’s not an investment thesis; it’s a physics problem.

Searching for a Map in a World Made of Code

Before you can understand a revolution, you have to understand the world it’s trying to overthrow.

And before you can chart a new territory, you have to look at the old maps, if only to see where they lead you astray.

The story of money is the story of a search for certainty in an uncertain world, a multi-millennia-long effort to find a technology that would allow one human to reliably store the value of their labor and trade it with another. To understand what happens when a digital, absolutely scarce object crashes into the global economy, we first have to ask a question so simple it sounds childish: What is money, anyway?

I’ve tried answering that question (and many others) on Robert Breedlove’s What Is Money podcast.

The first people who tried to draw this map weren’t economists; they were just trying to run a functioning society without it descending into chaos.

More than two thousand years ago, Aristotle laid out the specs for perfect money:

For something to work well as money, he said, it needed to be a few things. It had to be durable, so it wouldn’t rot or rust. It had to be portable, so you could carry it around without a team of oxen. It had to be divisible, so you could make change for a goat. That’s critical. And, also important, it needed to have some kind of intrinsic value… it had to be desirable for its own sake. For most of history, gold and silver fit this description better than anything else. They were the beta test that ran for three thousand years. They weren't perfect, but they were the best map we had to wealth storage.

For centuries, that was pretty much that. Money was a shiny metal you dug out of the ground. But then, in the 19th century, in the coffee houses of Vienna, a man named Carl Menger had a profound insight that would form the bedrock of the Austrian School of economics.

Menger watched people in the marketplace and realized that the story of money wasn't about governments or kings decreeing what people should use. It was an emergent phenomenon, like a footpath forming across a field.

Menger’s idea was called "saleability." Imagine a village barter economy. A chicken farmer wants to buy a pair of shoes. The shoemaker, however, doesn’t want chickens. The farmer is stuck. But then he realizes that the baker, who everyone visits, always needs wheat. Even though the farmer doesn't want to bake bread, he trades his chickens for a sack of wheat. Why? Because he knows the sack of wheat is more saleable than the chickens. He has a better chance of trading the wheat with the shoemaker, or with anyone else, for what he actually wants.

Slowly, Menger argued, everyone in the society converges on the single most saleable good. It’s not necessarily the most useful, but the one that is most widely accepted, the one that loses the least value when you trade it again. That good becomes money.

Money isn’t a government invention; it’s a market discovery. It’s the spontaneous solution to a massive information problem. It is the good that best serves as a store of value across time and a medium of exchange across space. This was a radical idea: money was a technology that the market itself invented to solve a problem. It planted a flag for a new way of thinking, a way that saw money not as a political tool, but as a social one.

The Math of Money

And then there’s the equation everyone learns in Econ 101, the one that feels like it has the reassuring certainty of physics: MV=PQ.

The Money Supply (M) times the Velocity of money (V—how many times a dollar changes hands) equals the Price Level (P) times the Quantity of goods and services (Q).

It’s an identity, a truism.

All the money, times how fast it’s spent, has to equal the value of everything that was bought. For decades, this equation was the primary map used by central bankers. Their main lever was M, the money supply. By increasing or decreasing M, they believed they could steer the economy, influencing prices and output. The entire theory of Quantitative Easing was a bet on this equation. By massively increasing M, they hoped to get people spending again and prop up a failing system.

But the equation has a hidden secret.

Its implications change entirely depending on which variable you think is the most stubborn. The central bankers assumed they could control M. But what if a new kind of money appeared where M wasn't just controlled, but was fixed, finite, and its future issuance was known to all participants with mathematical precision?

Messes with the math a bit, doesn’t it?

What would that do to the other variables? If the quantity of money (M) is fixed, then any increase in economic output (Q) or any change in the desire to hold money (a decrease in V) must, by mathematical necessity, be reflected in a change in the price level (P).

In a world of fixed money and growing productivity, prices would have to fall. Asset-owning “Masters of the Universe” MUCH prefer the intentional inflation of endless central bank printing. The inflationary force constantly pulls economic energy from renters to owners, just like the asset owners want.

If they let prices fall with technology, the world would become deflationary. The map of MV=PQ is still valid, but it suddenly points to a completely different destination than the one its creators intended.

For the first decade of Bitcoin’s existence, these old maps were all anyone had. They were like trying to navigate the sky with a map of the ocean. Most economists dismissed Bitcoin as a fad, a fraud, or at best, a niche curiosity. It didn’t fit their models. It had no "intrinsic value" like gold; you couldn't make jewelry out of it. It wasn't backed by a government, so it failed the political test. It was an anomaly, and the easiest way to deal with an anomaly is to ignore it.

But a small handful of people couldn't ignore it. They sensed that the anomaly was the story. The first person to try and draw a new map, to chart this strange new continent, wasn't an academic in an ivy-covered tower. He was an anonymous institutional investor from the Netherlands.

He went by the pseudonym "PlanB" In March of 2019, he published an article called "Modeling Bitcoin's Value with Scarcity".

PlanB’s insight was Menger’s theory of saleability, but supercharged for the digital age. He looked at what made gold a good monetary asset for millennia and landed on its scarcity. But he gave it a number. He used a ratio called Stock-to-Flow. The "stock" is the total amount of a commodity that already exists. The "flow" is the new amount that is produced each year. The ratio tells you how many years of current production it would take to replicate the existing stockpile.

Think of it this way. For gold, the total amount that has ever been mined (the stock) is about 200,000 tons. The annual new production (the flow) is about 3,000 tons. So gold’s Stock-to-Flow ratio is around 66 (200,000 / 3,000). It would take 66 years of mining to dig up the amount of gold that already exists. This is what makes it "hard" money. It's difficult to inflate the supply. For industrial commodities like copper or zinc, the ratio is barely above 1. If demand surges, miners can quickly increase production and flood the market, crashing the price.

Their scarcity is a fiction.

Gold's scarcity is real. But it isn’t absolute.

PlanB's stroke of genius was to apply this same logic to Bitcoin. Bitcoin’s stock was the number of coins already mined. Its flow was the number of new coins being created with each new block. The magic was that both of these numbers were not just known, but predetermined. And because of the "halving", the event every four years where the new supply is cut in half, Bitcoin’s Stock-to-Flow ratio was programmed to increase on a predictable schedule. Every four years, it would roughly double, making Bitcoin algorithmically "harder" and more scarce.

When PlanB plotted the market value of Bitcoin against its rising Stock-to-Flow ratio, the result was what many “Bitcoin Maxis” feel in their bones about $BTC price. The points formed an almost perfect, straight line on a logarithmic chart, spanning nearly a decade of data. The model seemed to explain Bitcoin’s seemingly chaotic price movements with a single, elegant variable: scarcity. It suggested that for every time the S2F ratio doubled, the market value of Bitcoin increased by an order of magnitude. It was the first coherent, data-driven attempt to value Bitcoin on its own terms.

The Stock-to-Flow model went viral and derivatives of did too. For believers, it was a revelation, a prophecy written in mathematics. It provided a framework, a sense of order in the chaos. It predicted a future price for Bitcoin so high it seemed absurd, but it was based on a logic that was hard to dismiss. The map, it seemed, had been found.

Of course, the model had its critics, and their arguments were powerful. Correlation does not equal causation. Was the model truly capturing a fundamental law of Bitcoin's value, or was it just a beautiful statistical coincidence, a curve-fitting exercise on an asset that had been in a near-uninterrupted bull market for its entire existence? Any asset that goes up exponentially will correlate with any other line that goes up exponentially, they say. The math agrees. The model, they argue, was a self-fulfilling prophecy at best, and a dangerous oversimplification at worst. It was a map of a single coastline, drawn during a high tide. No one knew what would happen when the tide went out. PlanB’s work was a landmark, a brilliant first draft. But the territory was stranger than even his model could capture.

If Bitcoin isn’t just a commodity to be measured by its flow, then what is it?

The search for an analogy, for something in the old world that behaves like this new thing, became a parlor game for financial thinkers.

Is it like a piece of fine art?

Is it like a plot of land? Michael Saylor of Strategy tends to think of Bitcoin as the scarcest real estate in the history of mankind.

Let's consider a Picasso. There are a finite number of them. The artist is dead; he will not be making any more. The supply is perfectly inelastic. And as global wealth has increased, the price of a Picasso has skyrocketed. This looks promising. It’s an asset whose value is derived almost entirely from its scarcity and desirability. But the analogy quickly breaks down from here. You can’t divide a Picasso into a hundred million pieces and use one of those pieces to buy a cup of coffee. You can't even be sure one Picasso is as good as another; they aren’t fungible. And teleporting it to a buyer in Hong Kong involves insurance, armored cars, and customs forms, not the click of a button. Art is a store of value for the ultra-rich, but it is not, and can never be, money for the world.

What about land? The island of Manhattan is a finite resource. As the demand to live and work in one of the world’s great commercial hubs has grown, the value of that land has done incredible things. Its supply is fixed. But again, the analogy is flawed. You can’t move Manhattan. It is the definition of immobile. It’s also not perfectly fungible. That means a plot on Wall Street is not the same as a plot in Harlem. And its value is tied inextricably to the health and success of the city and country built upon it. Land is a powerful store of value, but it is local and illiquid. And, they DO make more it. Contrary to the saying. Singapore, the Battery Park area of NYC, etc… We make land all the time.

This is the crux of the problem, and why the old maps fail.

Bitcoin is not like gold, or art, or land.

It is a strange and unprecedented fusion of the best properties of all of them. It has the absolute scarcity of a Picasso, but it is perfectly fungible. One Bitcoin is identical to any other. It is highly divisible, down to a one-hundred-millionth of a coin, making it suitable for transactions of any size. It is supremely portable, a multi-billion-dollar fortune that can be stored in a sequence of twelve words in a person’s memory and moved across the planet in minutes. And its value is not tied to any single jurisdiction, corporation, or physical location. It is native to the internet, a global asset for a global, digital age.

The classical theories of money give us a powerful vocabulary for understanding what properties a monetary good should have. The Austrian school gives us a framework for how a market might choose that good based on saleability. The Quantity Theory of Money gives us an equation that hints at the strange, deflationary consequences of a fixed money supply. The first-pass models like Stock-to-Flow give us a tantalizing but perhaps deceptive correlation between algorithmic scarcity and market price. And the analogies to existing scarce assets show us what Bitcoin is like, but more importantly, how it is different from everything that has come before.

Each map shows us a piece of the puzzle.

But none of them shows us the whole picture.

None of them were drawn to account for the invention of absolute, digital scarcity. To truly understand what happens next, we have to put these partial maps away and begin to draw our own.

We must build a model based not on what Bitcoin is like, but on what it is: a perfectly inelastic container being asked to absorb a rising ocean of liquid energy.

Onto Part II!

Unstoppable Money Printer Meets Absolute Scarcity - Part II

The problem with trying to understand a phenomenon like Bitcoin is that our brains, and the economic models our brains have built, are creatures of an elastic world.

Friends: in addition to the 17% discount for becoming annual paid members, we are excited to announce an additional 10% discount when paying with Bitcoin. Reach out to me, these discounts stack on top of each other!

👋 Thank you for reading Wealth Systems.

I want to learn what topics interest you, so connect with me on X.

…or you can find me on LNKD if that’s your deal.

I started Wealth Systems in 2023 to share the systems, technology, and mindsets that I encountered on Wall Street. I am a Wall St banker became ₿itcoin nerd, ML engineer & family office investor.

💡The BIG IDEA is share practical knowledge so we can each build and optimize our own wealth engines and combine them into a wealth system.

To help continue our growth please Like, Comment and Share this.

NOTE: The content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, accounting, or legal advice. The author and the blog owner cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information presented and are not responsible for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from the use of such information.

All information on this site is provided 'as is', with no guarantee of completeness, accuracy, timeliness, or of the results obtained from the use of this information, and without warranty of any kind, express or implied. The opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the site or its associates.

Any investments, trades, speculations, or decisions made on the basis of any information found on this site, expressed or implied herein, are committed at your own risk, financial or otherwise. Readers are advised to conduct their own independent research into individual stocks before making a purchase decision. In addition, investors are advised that past stock performance is no guarantee of future price appreciation.

The author is not a broker/dealer, not an investment advisor, and has no access to non-public information about publicly traded companies. This is not a place for the giving or receiving of financial advice, advice concerning investment decisions, or tax or legal advice. The author is not regulated by any financial authority.

By using this blog, you agree to hold the author and the blog owner harmless and to completely release them from any and all liabilities due to any and all losses, damages, or injuries as a result of any investment decisions you make based on information provided on this site.

Please consult with a certified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

A fantastic piece of work here Matt